By Dr. Barna Szabó

Engineering Software Research and Development, Inc.

St. Louis, Missouri USA

I am often asked to comment on how it is possible that, although everybody agrees simulation governance is a good idea, it is not being practiced — or, as Shakespeare would put it more elegantly, “more honour’d in the breach than the observance.” — The short answer is that changing minds and habits is hard. A more detailed explanation follows.

Simulation Governance

The concept of simulation governance was introduced at the International Workshop on Verification and Validation in Computational Science at the University of Notre Dame in 2011 [1] and subsequently published in a refereed journal in 2012 [2].

At the 2017 NAFEMS World Congress in Stockholm, simulation governance was identified as the first of eight “big issues” in numerical simulation. NAFEMS is an acronym of a British organization called the National Agency for Finite Element Methods and Standards, founded in 1983. This organization has evolved to serve a global modeling and simulation community. It has a dedicated working group called the Simulation Governance and Management Working Group (SGMWG).

The idea of simulation governance is simple and self-evident: management is responsible for exercising command and control over all aspects of numerical simulation. The real challenge lies in what comes next. To achieve reliable and credible simulation outcomes, management must:

- Define clear objectives for each simulation project.

- State the technical requirements, including standards for model formulation, verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification (VVUQ).

- Make the necessary organizational changes, such as establishing policies, procedures, and allocating resources.

To understand the nature of these challenges, we must have a clear understanding of what a mathematical model is. This is described next.

Mathematical Models

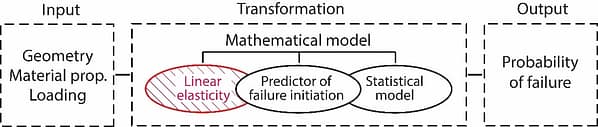

A mathematical model is, essentially, a transformation of one set of data (the input) into the quantities of interest (the output). The transformation comprises a set of operators. The following relationships provide a high-level description of a mathematical model:

\boldsymbol D\xrightarrow[(I,\boldsymbol p)]{}\boldsymbol F\Longrightarrow \boldsymbol F_{num},\quad (\boldsymbol D, \boldsymbol p) \in ℂ, \quad | \boldsymbol F - \boldsymbol F_{num} | \le \tau|\boldsymbol F| \quad (1)where D represents the input data, and F represents the quantities of interest. The right arrow represents the transformation. The letters I and p under the right arrow indicate that the transformation involves an idealization (I) as well as parameters (physical properties) p that are determined by calibration. The double line arrow indicates that, in general, the exact value of F is not known, only an approximate value, computed by a numerical method and denoted by Fnum is known.

Idealizations are based on subject matter expertise and personal preferences. The errors associated with idealizations are called model form errors whereas the errors associated with numerical approximation are called discretization errors [3].

Calibration entails inferring parameters from physical experiments. Invariably, there are limitations on the available data. The set of intervals on which calibration data is available, together with the assumptions incorporated in the mathematical model, constitutes the domain of calibration ℂ. The domain of calibration is an essential attribute of a mathematical model. A model is validated within its calibration domain. Predictions can be wildly off when D and/or p lie outside of ℂ. One of the goals of model development is to ensure that the domain of calibration is large enough to encompass all intended applications of the model.

The statement in Equation (1):

| \boldsymbol F - \boldsymbol F_{num} | \le \tau|\boldsymbol F|indicates that the numerical error has to be under control. This requirement is usually given in terms of the maximum acceptable relative error τ which is usually between 0.01 and 0.05. The goal of solution verification is to show that the relative errors are within permissible bounds.

Time Dependence

The idealization (I) and the domain of calibration (ℂ) are time-dependent: model development projects must account for the possibility that new ideas will be proposed, implying that the choice of model (e.g., the predictor and statistical model) will evolve over time. It is also likely that new calibration data will become available, leading to changes in the domain of calibration. Therefore, model development projects are open-ended. An important objective of simulation governance is to provide a hospitable environment for the evolutionary development of mathematical models.

The Transformation: Example

Consider the scenario where an aerospace corporation is planning to use an advanced composite material system to design a new airframe. In the absence of prior experience with this material, new design rules must be developed.

In this case, the transformation, represented by the right arrow in Equation (1), comprises three operators: One operator produces the solution of a problem of linear elasticity, or more generally, continuum mechanics. The second operator uses the solution from the first to predict failure initiation. The third operator accounts for the statistical dispersion of failure events. This is illustrated schematically in Figure 1.

The first operator, linear elasticity, has been extensively researched and thoroughly documented. It forms a fundamental part of the knowledge base that professionals rely on. The assumptions incorporated in this operator are called hardcore assumptions.

Model development focuses on the second and third operators. The second operator, which predicts failure initiation, and the third operator, which predicts the probability of outcome, belong to respective families of competing hypotheses. The model development process seeks to identify the members of those families that exhibit the strongest predictive performance [3]. The assumptions incorporated in these operators are called auxiliary hypotheses.

The formulation of auxiliary hypotheses is a creative activity that must be subjected to a process of objective evaluation. This is a key task in model development. For example, in the World Wide Failure Exercise II (WWFE), twelve competing predictors of failure were proposed [4]. Unfortunately, WWFE lacked the procedures needed for objectively ranking those predictors, and thus the effort failed to meet its stated goals.

Classification

Model development projects are classified in reference [3] as follows:

- Progressive: The size of the domain of calibration is increasing.

- Stagnant: The size of the domain of calibration is not increasing. Notable example: Linear Elastic Fracture Mechanics.

- Improper: The auxiliary hypotheses do not conform to the hardcore assumptions, and/or the model form errors are not controlled, and/or the problem-solving method does not have the capability to estimate and control the discretization errors in the quantities of interest.

Currently, most model development projects qualify as improper. The primary reason is that the necessary conditions for achieving their objectives have not been established. In most organizations, management lacks a clear understanding of what a proper model development project entails and therefore fails to establish technical requirements to separately control model form and discretization errors or to properly specify the domain of calibration.

Compounding this issue, many organizations still rely on outdated finite element software that is not equipped to support verification and validation practices in industrial settings. In the absence of simulation governance, these technical prerequisites remain absent, rendering project failure virtually certain.

Why is Simulation Governance More Honored in the Breach Than the Observance?

I believe the answer is that the major organizations that rely on numerical simulation—and bear both the costs of model development and the consequences of erroneous decisions—have not formulated sound technical requirements to ensure the reliability of predictions.

For example, NASA may state a problem as follows: Given a spacecraft, a mission, and a set of design rules, report all margins of safety within a 3 percent tolerance. The decision maker should have a high degree of confidence that the reported values do not exceed these tolerances. Such information is needed to certify that the applicable design rules are met.

NASA issued its Standard for Models and Simulations (NASA‑STD‑7009) in July 2008. This was one of several agency-wide responses to the 2003 Columbia accident. Updated most recently in 2024, the standard NASA‑STD‑7009B aims to reduce risks in decision-making based on modeling and simulation (M&S) by ensuring that results are credible, transparent, and reproducible. Credibility is defined in the document as the quality to elicit belief or trust in M&S results.

According to this standard, credibility is evaluated through two complementary assessments: an M&S Capability Assessment (development‑phase factors such as verification, validation, data pedigree, technical reviews, and process/product management) and an M&S Results Assessment (use‑phase factors such as input pedigree, uncertainty characterization, results robustness, use/analysis reviews, and process/product management).

NASA‑STD‑7009B does not provide decision makers with a pass/fail rule or even a single “credibility score.” Instead, it requires the decision maker to interpret two multidimensional assessments (Capability and Results) along with supporting documentation. None of this explicitly tells the decision maker whether the spacecraft should or should not be certified for the mission.

The aims of NASA‑STD‑7009B could have been achieved more directly if the standard had included technical requirements for model development—addressing formulation, validation, verification, ranking of alternative predictors, and definition of the calibration domain, as outlined in [3]. This would allow decision makers to trust predictions when the data and parameters (D, p) fall within the domain of calibration. Whereas credibility is a fuzzy concept, determining whether the condition (D, p) ℂ is satisfied is objective.

References

[1] Szabó, B. and Actis, R. Simulation governance: New technical requirements for software tools in computational solid mechanics. International Workshop on Verification and Validation in Computational Science, University of Notre Dame, 17-19 October 2011. [2] Szabó, B. and Actis, R. Simulation governance: Technical requirements for mechanical design. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 249, pp. 158-168, 2012. [3] Szabó, B. and Actis, R. The demarcation problem in the applied sciences. Computers & Mathematics with Applications, 162, pp. 206-214, 2024. [4] Kaddour, A. S., and Hinton, M. J. Maturity of 3D Failure Criteria for Fibre-Reinforced Composites: Comparison Between Theories and Experiments: Part B of WWFE-II,” J. Comp. Mats., 47, 925-966, 2013.Related Blogs:

- A Memo from the 5th Century BC

- Obstacles to Progress

- Why Finite Element Modeling is Not Numerical Simulation?

- XAI Will Force Clear Thinking About the Nature of Mathematical Models

- The Story of the P-version in a Nutshell

- Why Worry About Singularities?

- Questions About Singularities

- A Low-Hanging Fruit: Smart Engineering Simulation Applications

- The Demarcation Problem in the Engineering Sciences

- Model Development in the Engineering Sciences

- Certification by Analysis (CbA) – Are We There Yet?

- Not All Models Are Wrong

- Digital Twins

- Digital Transformation

- Simulation Governance

- Variational Crimes

- The Kuhn Cycle in the Engineering Sciences

- Finite Element Libraries: Mixing the “What” with the “How”

- A Critique of the World Wide Failure Exercise

- Meshless Methods

- Isogeometric Analysis (IGA)

- Chaos in the Brickyard Revisited

- Why Is Solution Verification Necessary?

- Variational Crimes and Refloating the Costa Concordia

- Lessons From a Failed Model Development Project

- Where Do You Get the Courage to Sign the Blueprint?

- Great Expectations: Agentic AI in Mechanical Engineering

- The Differences Between Calibration and Tuning

Serving the Numerical Simulation community since 1989

Serving the Numerical Simulation community since 1989

Leave a Reply

We appreciate your feedback!

You must be logged in to post a comment.